Anyone interested in the history of contemporary yoga should be familiar with Mark Singleton’s (Oxford University Press, 2010). In addition to being the most sophisticated history of modern yoga yet written, Yoga Body succeeded in reaching the practitioner community in ways extremely rare for a scholarly work. In so doing, it played a pivotal role in shifting the reigning self-understanding of North American yoga community away from blithe assumptions of representing a “5,000-year-old practice” and toward important questions regarding what it means to practice yoga in our society today.

|

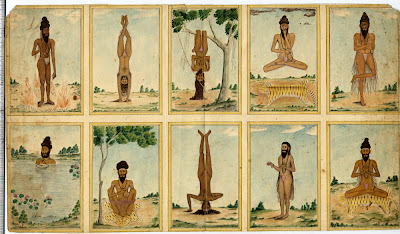

| Seven yogis under a banyan tree (1630-31) |

Now Mark is hoping to work with his friend and colleague, Jim Mallinson, on an edited volume of historic Indian texts tracing the evolution of yoga from the ancient through pre-modern periods. While grounded in scholarship, the book, entitled Roots of Yoga: A Sourcebook from the Indian Traditions, will be written for a general audience. Intended to be a resource for the English-speaking yoga community, Roots of Yoga will provide a source of original yogic texts (about half previously untranslated) unlike anything available today.

In order to produce Roots of Yoga, Mark and Jim need funding to cover their work and travel expenses. Given that the book will be aimed at practitioners, they can’t get academic grants. So, they’ve trying to raise $50K via Kickstarter. You can link to the campaign, which runs from July 11th – August 10th, by clicking here.

I feel strongly that the yoga community should do everything that we can to support this project. Mark and Jim are world-class scholars with years of experience studying and practicing yoga. They are fluent in the art of translating Sanskrit, specializing in yogic texts. Between them, they have a deep knowledge of the histories of both medieval and modern yoga, as well as of contemporary practice in both India and North America.

|

| R. Schmidt, Fakire und Fakirtum im alten und modernen Indien (1908) |

But: If they can’t raise the money, they can’t do the project.

So please take a moment and contribute to the Roots of Yoga Kickstarter campaign. Then spend a few more minutes asking all your yoga friends to do the same. Talk the project up at your local studio. Get it out there on Facebook, Twitter, or whatever your favorite social media platforms may be. If you care about yoga, I honestly believe this will prove to be an exceptionally valuable investment of your money and time.

_______________________________________________________

|

|

|

| Mark Singleton |

A week or so ago, I interviewed Jim and Mark via Skype to learn more about the project. Before getting into that conversation, however, here’s a bit more info on who these men are:

Mark Singleton holds a Ph.D in South Asian Religion from Cambridge University. In addition to the path-breaking Yoga Body, Mark published the first-ever edited volume on modern yoga, (Jean Byrne, co-editor; Routledge 2008). Another co-edited (with Ellen Goldberg) book, Gurus of Modern Yoga, is in production with Oxford University Press. With Jim Mallinson, Mark is currently launching a five-year research project at Oxford University to edit and translate the five earliest texts to teach Hatha yoga.

|

| Jim Mallinson |

Jim Mallinson holds a Ph.D. from Oxford University, where he studied with the world’s leading scholar of Tantra, Professor Alexis Sanderson. In 2007, he published a critical, annotated translation of , a 14th century text detailing a traditional Hatha yoga technique called Khecarimudra. He has also translated many other Sanskrit texts, including the yoga classics, the Gheranda Samhita and Shiva Samhita, parts of which are available for free download on YogaVidya.com.

Jim is also a documentary filmmaker, producing “The Beginner’s Guide to Yoga” for British national television and an independent feature documenting his paragliding expedition to an ancient Hindu temple in the Himalayas (editorial note: how badass can you get?). Other creative work in process includes memoir of the eight years he spent studying with itinerant yogis and ascetics in India; a documentary on “The Original Yogis at the Kumbh Mela,” and a collaboration with photographer Cambridge Jones on an illustrated history of yoga.

Carol: The yoga tradition is vast and diverse. How will you draw the boundaries of “yoga” in your project?

Jim: There’s an ongoing debate over what yoga is and isn’t. Obviously, we have to delineate somewhere.

Mark: We’re planning to prioritize texts that explicitly identify themselves as being part of the yoga tradition. We’ll also include Tantric texts that have a yoga component, as well as Upanishadic texts that may not self-identify as “yoga,” but contain evident precursors to later practices.

Jim: Physical yoga practices weren’t really developed until the early medieval period. No text refers to “Hatha yoga” prior to the 13th century Dattatreya Yoga Shastra. Still, we can look back and see where the physical practices came from with the benefit of hindsight.

For example, the Buddha mentions physical practices that would definitely qualify as Hatha yoga in the Pali Canon, but he didn’t call them that.

Carol: So, are you going to focus on the development of Hatha yoga in particular?

Jim: Yes – but not in the sense that the term has come to be understood in the modern period.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Theosophical Society and then Vivekananda posited a split between “Hatha” (physical) and “Raja” (mental) yoga, which is the framework that we’re familiar with today. I’d argue, however, that in the pre-modern era, this distinction between physical and mental yoga didn’t exist.

Mark: I agree. Hatha yoga was incorporated into lots of different yogic systems from 16th century onwards. Today, people assume that there’s always been a divide between physical and mental yoga – but historically, that doesn’t hold.

|

| Ascetic practicing various techniques of yoga and tapas (~1825) |

Carol: As you know, the history of Hatha yoga has been whitewashed quite a bit, with practices that were disturbing to modern Western (and middle-class Indian) sensibilities erased out of the picture. How will you negotiate the cultural politics involved in representing the past? (Note: If you don’t get where this question is coming from, check out (for example) Sinister Yogis by David Gordon White.)

Mark: Yes, it’s true; that sort of sanitizing of history has gone on. Even in books about Iyengar yoga, all that stuff is cast to the side. But historically, it’s there and cannot be ignored.

Jim: It would be very disingenuous to ignore what’s discomforting to contemporary sensibilities – these practices are central to the tradition. To pretend they’re not there would be to misrepresent it.

Mark: We can’t stop people from being offended. I’m not sure how some of this stuff will be received. Some of the practices may be interesting and appealing for what practitioners might want to do in America today. Others are not. I don’t see that as a reason to hide any of it.

|

| Yogirāj Jagannāth Dās, Haridwar Kumbh Melā, 2010 (photo: Jim Mallinson) |

In our commentaries on the texts, we can also help people understand what they may see as strange by explaining how it fits into the system as a whole. True, the Christian right will take it as more evidence of the Satanic nature of yoga, which is of course nonsense. But there’s nothing that can be done about that.

Jim: I’ve spent a lot of time with ascetics in India who do these sorts of practices – Basti, Khecarimudra , and so on. (Note: Khecarimudra involves progressively cutting the root of the tongue so that it’s able to be inserted up into the soft palate at the back of the throat; Basti includes squatting in water, drawing it in through the anus, and expelling it.) I think that we can make it clear that when they’re understood in their indigenous cultural context, they take on different meanings. For example, some of the yogis I know would see Basti in very much the same way that we see colonic cleansing.

Carol: How do you envision the structure of the book?

Mark: The book will be organized thematically, with sections on asana, pranayama, mudra, bindu, etc. Each will begin with a short introduction that provides historical context. We’ll also include notes to explain technical terms and other information that might useful to the general reader. We want make the book as user-friendly as possible.

|

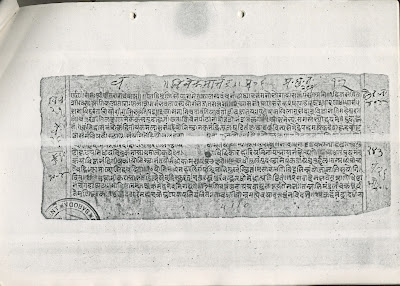

| Vivekamārtaṇḍa manuscript (1477) |

Carol: Will the book include new, previously untranslated material? If so, have you already located it, or do you have more research to do?

Mark: While it remains to be determined, it’s probably going to be about half previously and half newly translated texts.

Jim: We’ve already identified the texts that we want to translate – if we had to identify them from scratch, the project would take at least 7 years. That said, we may, of course, discover something new.

Carol: If you already know what you want to translate, why do you need to go to India? Couldn’t you just get photocopies and do the translations at home?

Mark: (laughs) Yeah, that would be nice – but we do need to go to the libraries. There will be lots of material to go through, and getting our selections right requires going to India and looking at what’s available firsthand. It will definitely take a trip or two.

Jim: Plus, getting the materials out of the libraries is a complex, bureaucratic process – there’s loads of forms to fill out and so on. And, while many of the librarians are really helpful, there are always those that need to be goaded to stop drinking chai and get on with it.

Carol: How will Roots of Yoga build on Yoga Body?

Mark: While it’s sometimes misinterpreted, the thesis of Yoga Body is not that yoga as we know it is only 100 years old. Rather, it’s a cultural history of the modern period. But there’s always a history prior to the one in question.

I don’t think that we should make a hard distinction between traditional and modern yoga. While it’s true that enormous new influences came in during the modern age – the Theosophical Society, yoga being exported from India, and so on – those boundaries are not hard and fast.

As soon as I finished Yoga Body, I wanted to extend my research back to the immediate pre-colonial period. This project will allow me to do that and more besides. I think it will complement Yoga Body well.

Carol: As yoga scholars, what motivates you to connect to the world of yoga practice – particularly when the North American yoga community is often (at least in my opinion) pretty non-intellectual, and sometimes even anti-intellectual?

Mark: It seems to me that practitioners today have only been exposed to a small part of the spectrum as to what yoga is and has been. The texts that we’ll compile in Roots of Yoga will point to many new possibilities.

There could be great benefit in entering into a conversation with the past through a collection like this. Hopefully, it will enable a depth of connection with it that hasn’t previously been easily available.

|

| Jim with his guru, Bālyogī Śrī Rām Bālak Dās, Haridwar Kumbh Melā, 2010 |

Jim: Unlike Mark, I’ve had very little contact with the world of contemporary Western practice. Mainly, I’ve hung out with traditional yogis and ascetics in India.

I’m fascinated, however, by how important the idea of “authenticity” seems to be in the yoga community today. And I think that it’s clear that there needs to be some better grounding in that regard. Some of these crazy controversies that flare up – like the recent claim that “yoga started as a sex cult” – show that there needs to be better, and more accessible information on the yoga tradition available.

Mark: This book will provide easy access to the sort of texts that I would have liked to have had when I first started practicing yoga. It will give practitioners a resource they can use to negotiate the field. It’ll enable them to get reliable answers as to what yoga has been historically by connecting them to original, primary texts.

Carol: Do you consider yourselves to be yoga practitioners?

Mark: Yes – I’ve practiced several schools of modern yoga. I started with Iyengar and Ashtanga, and later studied Satyananda, which is another modern tradition that’s more well-known in parts of Europe and Australia than the U.S. It’s also the method that’s represented in the largest teacher training school in northern India, and possibly in India as a whole.

So that combined with things that I’ve learned from various other places . . . whatever it means to be “a yoga practitioner” . . . yes, I do yoga of some sort.

|

| Jim practicing Nauli on the beach in Kerala |

Carol: To be clearer where I’m coming from with this question – it ties into the whole issue of authenticity, which, as you mentioned, is big in the yoga community. In practitioner circles, it’s very common to dismiss scholarly work (particularly when there’s disagreement with it!) on the grounds that scholars are not practitioners, and therefore don’t understand what they’re writing about in any meaningful way.

Mark: Yes, there is a strong discourse of bookish versus real knowledge. The very term “academic” is a term of abuse in certain practitioner circles.

I’m possibly prejudiced (and Jim is, too), but I believe that scholarship has enormous value in helping us understand what practice means – not just now, but what it has meant in the past. One fundamental way of pushing the boundaries of what the practice can be is through the process of serious inquiry provided by scholarship.

Carol: So, Jim: do you also consider yourself a yoga practitioner?

Jim: Yes. And I find it much easier to say I’m a “yoga practitioner” than to say I’m a “yogi.”

I spent most of my 20s wandering around India with yogis and ascetics, the sort that you’d see at the Kumbha Mela. Most of what they were practicing, I’d try. So, for example, I did the Khecarimudra practice, cutting my tongue away; I did Basti and all that – although it doesn’t actually float my boat that much. I learned asana, pranayama . . .

But now, I’ve got small children. And like many yogis in India, who tend to go through a period of intense practice for several years, and then rest on their laurels for awhile – I now just do a short practice everyday, and longer bouts periodically when I can.

|

| Coat of Arms: Oxford University |

Carol: You’re both English, and trained at the most elite universities in Britain. Do you consider yourself to be part of the lineage of British scholars that’s been studying yoga and related practices in India since the 18th century?

Mark: To some extent. There has been a lot of Orientalist bashing, and much is well justified. But there’s also a tendency to extend Said’s diagnosis of the violent, dominating, colonial gaze to include the work of European scholars who were studying Indian religions and making translations of texts in significantly different ways. (Note: If this reference doesn’t make sense, you can read about Edward Said’s seminal critique of “Orientalism” here.)

To some extent throughout my career, I have looked to this early European scholarship on India. And while its often quite flawed, I don’t necessarily see it as representing an Orientalist gaze. There is enormous benefit in cross-cultural study and exchange. And I don’t believe that there’s necessarily a hard and fast separation between cultures. Historically, there has always been learning across regional boundaries. There has always been intercultural exchange.

|

| R. Schmidt, Fakire und Fakirtum im alten und modernen Indien (1908) |

Jim: I don’t see myself in a direct lineage from Oxford scholars of the past. I do, however, see myself as part of the tradition of study developed by my thesis supervisor, . His work revolutionized study of Tantra, really opening the field up. To a certain extent, I feel that that’s what I, along with several of his other students, are starting to do with yoga – Hatha yoga in particular.

Remember – Roots of Yoga can’t be published without YOUR help!

Contribute to the Kickstarter campaign by clicking here.

Contribute to the Kickstarter campaign by clicking here.

_______________________________________________________

Additional info on images:

Seven yogis under a banyan tree. Mughal, dated 1630-31, in the collection of the British Museum (1941,0712,0.5).

R. Schmidt (1908), Fakire und Fakirtum im alten und modernen Indien: Yoga-Lehre und Yoga-Praxis nach den indischen Originalquellen (Berlin: Hermann Barsdorf). The āsana on the left is guptāsana, the one on the right is paścimattānāsana.

Yogi in Kukkuṭāsana on the prākāra wall of the Mallikārjuna temple at Srisailam in Andhra Pradesh, c. 1510. The oldest known image of a yogi in a non-seated āsana. Copyright Rob Linrothe.

Ascetic practicing yoga and tapas: Andhra Pradesh, in the collection of the British Museum (2007, 3005.4).

The first folio of a manuscript of the Vivekamārtaṇḍa dated to 1477 CE and in the Baroda Oriental Institute Library. This text was expanded to become the Gorakṣasaṃhitā/śataka.

Jim with his guru, Bālyogī Śrī Rām Bālak Dās: photo credit - Chris Giri.

8 comments: