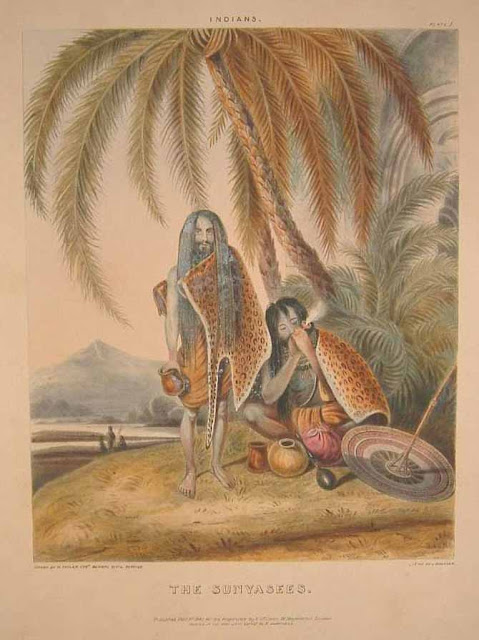

Searching through Google Images last night for pics to illustrate my latest post at Elephant Journal ("The Oprah-fication of Patanjali: Culturally Homogenizing the Yoga Sutra" - please check it out if you haven't yet!), I stumbled across an incredible web page full of historical photos and prints of Hindu fakirs and ascetics from the 1700s-1960s.

On further investigation, I figured out that this collection is part of a much larger set of online resources put together by Dr. Frances W. Pritchett at Columbia University. Given that there's nothing that says that these images can't be shared online, I figured that it would be OK to post some of them, along with some personal ruminations, here.

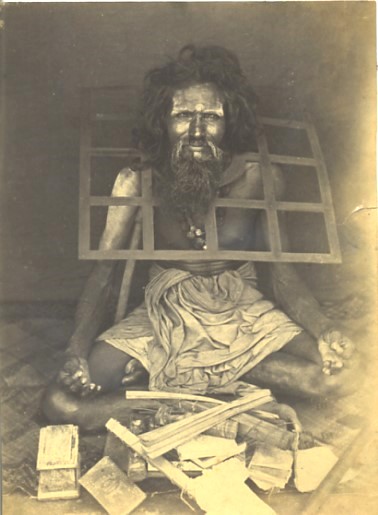

This print is labeled "'The Sunyasees,' by William Taylor of the Bengal Civil Service, 1842." While obviously a highly Europeanized rendition, there's something about the weirdness of English pastoral feeling infused into an illustration of Hindu mendicants smoking bhang in tiger skins that I really like.

Many of the images are not so soothing, however. I find this one, labeled "An ascetic with his full traveling equipment: a photo by a soldier, World War II," full-stop arresting:

Note again the tiger skin. (An interesting article that briefly explains their significance, accompanied by an absolutely stunning late 19th century print, can be accessed here).

I thought about using this photo in my EJ post, but somehow, in that overly loud and crass forum, I thought that it would be disrespectful. So I didn't post it there. But I did want to share it, because I find it quite powerful.

I feel that this is not an image that should be taken lightly. I don't know remotely enough about India and Hinduism to understand its significance, but that's precisely what I like about it. It really drives home the reality of cultural difference - as an American who's never even been to Asia, everything that's symbolized and represented here is completely foreign to my experience.

And it blows my mind that it was taken during World War II.

Here is another image that just stops me in my tracks. As you can read faintly under the photo, it's labeled "Hermit at Gem Lake doing penance--exposed to mid-day sun and intense fires--Mt. Abu, India. Copyright 1903 by Underwood & Underwood."

1903 is really not all that long ago - heck, I had grandparents alive then. But there's something about this photo that feels to me very ancient. It conjures up something like the feelings I had as a young child back in Sunday School looking at photos of Jerusalem and hearing wild and sacred stories of men being swallowed by whales, floods almost destroying the earth, seas parting, the dead rising, casting out demons, and walking on water.

In other words, all of the cultural referents that were hard-wired into me at an early age were Judeo-Christian. This is not good or bad; it just is. But it is significant.

I can work to understand Hinduism, traditional yogic austerities, or whatever. But it's not encoded into my cultural DNA.

Even in today's highly globalized, mulit-culti world, I still feel very conscious of being a Westerner.

Here are two much more disturbing images. I would be lying if I didn't admit that they rouse up some rather stereotypically Western feelings of horror that such practices are considered worthy austerities.

Yet it's also true that this gut-level sense of repugnance is genuinely mixed with a feeling of wonder and respect for a religion and culture that I recognize that I really don't understand - at all.

|

||||

| "An ascetic with a metal grid welded around his neck so that he can never lie down; photo, late 1800s." |

|

| "A photo by T. A. Rust, c.1880s, of an ascetic who constantly keeps his arms extended upward." |

The next image is not so disturbing, but I think that there is something terribly poignant about it. I wonder who these men were - what their lives were like - how did they think about themselves and the world - and - what's the connection to someone like me?

I don't know even the beginning of the answers to any of these questions.

|

| "Fakirs, Bombay," a photo by Taurines, c.1880s" |

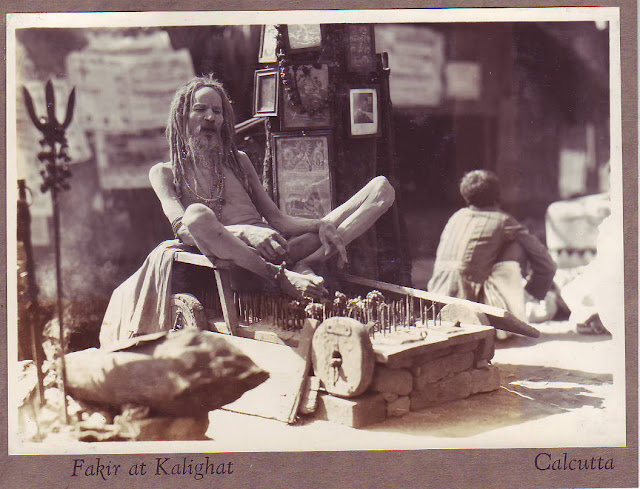

These next two photos illustrate the phenomena of yogis and fakirs turning into an odd sort of - not exactly tourist attraction, but perhaps exotic street performance. (Mark Singleton discusses this in his book, Yoga Body, in a section that I reference in my EJ post mentioned above.)

This "stereoscopic" presentation of a man lying on the classic "bed of nails" may conjure up odd associations for those of us old enough to remember the viewfinders that we may have had as children. For those who never had them or are too young to remember, these were binocular-like contraptions that you would put a double-imaged slide into in order to view images in 3-D. (Positively prehistoric technology by today's standards, to say the least! But I remember them well. I used to really be really excited to buy packs of viewfinder slides to look at on family vacations to Yellowstone and places like that.)

|

| "Hindu devotee doing penance on a bed of spikes near the shrine of Kali, Calcutta"; a stereo view, c.1900" |

However, needless to say, my childhood viewfinder slides never contained images like that . . .

The next photo gives me the sense that the ascetic pictured is engaged in some sort of street performance - there is something very posed feeling about it, with the trident on the left and the pillar with garlands and framed pictures in back.

|

| "An ascetic on a bed of nails, Calcutta, c.1920s" |

This morphing from holy man to object of European "voyeuristic fascination" is also disturbing -- although, unlike the radical austerities pictured above, in a non-visceral way. But it makes me think of how some tribal peoples were violently opposed to being photographed by Westerners because they believed that the process stole something of their souls.

From Beds of Nails to Contemporary Yoga

Of course, we've all heard of the proverbial "bed of nails" - but I, at least, had never seen such photos of them before. (There are quite a few more posted on the same site.) And certainly, I'd never quite so directly connected the dots from them to anything that I think of as "yoga" prior to reflecting on these images.

Which gets us into the whole "what is yoga" debate - which on the one hand is so fascinating, but on the other so difficult. Because it's impossible to give a single comprehensive answer. And, there's so many people that have such strong - and strongly differing - takes on it.

The most recent comment on my EJ post was from someone who was clearly irate because he felt that today's regular practice was once again being dissed. Which wasn't at all my intent - in fact, it's rather ironic, because I see myself as a passionate advocate of contemporary, syncretic, post-modern yoga.

But I also respect people who take ancient texts and traditions seriously. Who devote themselves to trying to understand and engage in practices that have always remained quite foreign to mainstream American society.

What bothers me (and this was the point of the EJ post) is blurring everything together so much that there's no sense that what we might be doing today - powerful, worthy, and wonderful as it may be - is essentially the same as what yogis were doing in India in the past. Muddling everything together in this way - which, it seems to me, is the default cultural perspective in at least a lot of the North American yoga community - strikes me as a tremendous loss.

Our world grows smaller to the extent that our capacity to recognize and respect cultural, religious, and yes, even spiritual difference shrinks.

And I hate that. I want the world to remain big - open, diverse, and mysterious. I look at these photos and recognize how much I don't know. And I love that.

To me, this sort of not knowing feels like a gateway to an ever-expanding universe of possibilities.

14 comments: