When I first stumbled on Yoga 2.0, I glanced at it briefly and dismissed it as wacko.

But when I detached from my everyday busy-ness enough to really read it, I quickly started to believe it was brilliant.

Moving onward, I got annoyed, and once again dismissed it, this time as overly romantic. But then I re-engaged, and found it to be meaty.

Now that I’ve read the whole book and had time to digest it, I find it nourishing. So, I’m hoping that other serious yoga practitioners will muster the time and energy to bite into this quirkily unique enigma of a book.

Be forewarned, it’s not an easy read. Authors Matthew Remski and Scott Petrie state up front that Yoga 2.0 “is not an introductory text.” And truly, those who don’t have a feel for yoga in their bones, as well as some “familiarity with the basic structure of yogic thought and history,” may be utterly confounded by it.

But practitioners seeking to broaden and deepen their practice should check it out. Because the book itself works as sort of a crazy wisdom practice; a melding of evolutionary theory, postmodern irony, and heart-centered sincerity seeking to connect us to our life source by tapping into yoga’s shamanic roots.

Fail. Fail. Fail. REBOOT

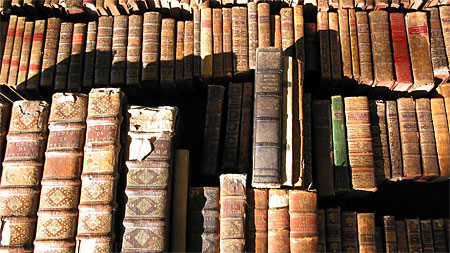

Yoga 2.0 insists that it’s long past time to break out of ossified conceptions of “yoga”; whether they are remote and exotic (e.g., artificially canonized “sacred texts”) or popular and taken-for-granted (e.g., glitzy yoga videos).

“2.0” invokes the rapid evolution of cyberspace. Just as the “read-only internet pages of ten years ago (‘Internet 1.0’)” morphed into the interactive web of today, our relationship to yoga needs to shift (and quickly, as the world is in crisis) from one of external authority to internal dynamism:

Yoga 1.0 is history. It is a book on the shelf, and perhaps a lecture talking about the book. Yoga 2.0 is a conversation. 2.0 invokes a move toward empowerment, interactivity, and relationship in its transmission.

Searching for authenticity outside ourselves, we turn yogic texts into false idols that we pretend to venerate, but don’t truly derive any juice from:

Yoga Sutras, Hatha Yoga Pradapika, Yoga Vashistha, Gheranda Samihita: all are extractions from dusty libraries that have gained value more through academic than practical attention. Going back another layer, the pages from which the mostly German professors translated were themselves extracted from the oral tradition. So any current book on yoga is probably a 10th generation extraction, with prana draining away with each printing and recension.

Habituated to hollow representations, we continue to create more and more of them in the name of spreading the supposed “Truth” of “Yoga.” This sets up “a smoke screen behind which all sort of mediocrities and outrages can safely hide”: Yoga magazines pretending to be “more than glorified IKEA catalogs,” self-promoting hucksters pretending to be traditional Indian gurus, privileged Americans pretending to be buying a bit of enlightenment by New Age-y consumption.

“’Yoga,’” accuse Remski and Petrie, “makes culturally adrift denizens of postmodernity fawn over just about anyone in a dhoti and sandals.”

As humorous, pathetic, or simply lost as we may be, however, that’s far from the end of the story. Because despite such denunciations, Yoga 2.0 is at heart a deeply hopeful work. It recognizes our post-modern predicament: awash in the confusing complexity of the modern world, adrift without our old faith in the power of Enlightenment rationality and science to propel us into a better future. But it embodies a hope that other, more creative and mysterious powers are available for us to work with if we only tap them.

And yoga – worked skillfully – is a tool for tapping these powers, “a Swiss army knife of the bodymind.” Practiced at the cutting edge, yoga enables us to slice through the layers of social conditioning that disconnect us from our life source.

Evolution and Integration

Worked this way, yoga reconnects us to the shamanic energies that originally fueled its creation.

To heal our selves and our world, however, this reconnection must also be an integration. Remski and Petrie are not traditionalists, urging us to abandon the present for some supposedly unchanging ideal. Instead, they are evolutionists, calling us to embrace everything from the ancient to the postmodern in the ever-changing immediacy of life.

Yoga 2.0 situates this vision of yoga as evolution in a short but sweeping story that takes us from the primordial to the present. Presented as allegory rather than analysis, it resists simple summation. Nonetheless, I’ll present a bit to provide some sense of the rich set of ideas at play.

The story starts back in hunter-gatherer era, the time of the “bicameral mind.” Human beings are so completely connected to nature that “it’s impossible to tell where the world ends and where you begin.” Meditation begins as a tool of the hunter, a necessity of life integrated with killing and death.

(Interestingly, ahimsa (the yogic principle of non-violence) comes later, with the development of agricultural society. The primordial roots of yoga, however, remain connected to the energies of the hunter – like us, it keeps its fang-teeth as civilization progresses.)

As human society becomes more complex, the unitary consciousness of the bicameral mind necessarily fragments. Different tribes develop, encounter each another, and discover the fact of cultural difference: “their” ways are not “ours.”

While our first instinct is to destroy “the other” for the audacity of being different (a reaction that’s still, of course, all-too-present), over time we generally learn acceptance. Dealing with difference, however, requires recognizing the particularity of our own culture. Consequently, the human mind develops the capacity for “holding and considering different and even opposing points of view” simultaneously.

While this is a good thing, it necessarily cuts our collective connection to nature. The days of simply living according to instinct are over.

Consequently, shamans emerge as specialists of “prayer and magic” – holy men and women capable of reconnecting the tribe back to the primordial source.

Time goes on; even more complex societies develop. Spirituality becomes codified as religion. Priests and Brahmins emerge as religious specialists, dedicated to maintaining their buildings, personnel, dogmas and rituals.

If the yoga of the shaman is wild and primordial, the yoga of the priesthood is civilized and polite. It supports the social order and helps people cope with it. As such, it’s useful but not transformative. While quite appealing to most people, resisters and shamans want more:

Spirituality and bureaucracy begin to mirror each other, while the old yogi watches calmly from his outcaste hut, a machete in his hand.

The story continues on through the birth of Buddhism and the emergence of the Bhagavad-Gita. Each represents a particular paradigm of consciousness, and, consequently, a distinct way of practicing yoga. Fundamentally, however, the narrative continues to elaborate the claim that while consciousness necessarily becomes more complex in concert with society, yoga offers a means of integrating these accreting layers of consciousness with the primordial force of life.

Confronting Postmodern Crisis

Our contemporary situation is symbolized by the BP oil spill:

When we look at the pelican coated with crude oil, blinking its bloodshot eyes through a black slick, its feet glued to the plywood of its improvised cage, we receive a subconscious image of our own bodies, so slathered with self-consciousness and so abused by our extractive manias that we cannot breathe, let alone fly.

All of the externally imposed imagery that we internalize every day keeps us – like the bird – unable to experience our own nature.

How do we, right now, break into the contemporary body – so hard to see beneath the mirrors, cosmetics, images, self-images, magazines, and flatscreens – to fully experience and describe this body, this life?

By connecting us to our own bodies, yoga cuts through the layers of social conditioning and self-consciousness that keep us trapped in a truncated experience of life. And today, as all of nature is in crisis, direct connection with life is critically important – without it, we won’t even grasp what we’re losing until it’s gone.

Practiced as postmodern shamanism, yoga is a weapon for fighting this destruction, a means of pumping prana back into our selves and our world.

The supple cacophony of jungle, forest, and ocean has been overwhelmed by screaming jets, HVAC fans, jackhammers, 2-stoke engines, and white computer noise. The yogi’s typical response to modern racket is to seek silence. But the animals with whom she shares her shamanic heart have always struck their poses with cries of danger, self-assertion, or savage love. Let us then reawaken our asanas – and ancient selves – with calls and caws, hoots and howls.

While I did have some quibbles with the book – some of it seemed overly romanticized, unnecessarily dense, or excessively self-conscious – ultimately I was charmed by this vision and this call.

Because really, what else is to be done? Whether yoga (or anything else) can stop environmental devastation, I don’t know. But I share the belief that it’s a tool that can connect us to the creative energies of life, and that we need this connection to have hope of healing ourselves and our world.

|

||||||

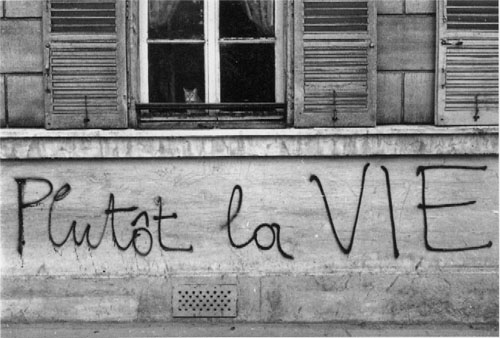

| "We Prefer Life": Paris, 1968 |

Yoga 2.0 is available for purchase through the book website, which you can access by clicking here.