I know, I know. Most everyone who even caught a whiff of the acrid smoke generated by the fire that burst out over the launch of Tara Stiles' last summer doesn’t want to go anywhere near that topic again. Even if you weren’t singed by the sparks or upset by the flame throwing, you probably ended up feeling burned out by the experience. As a participant-observer in this strange new culture of contemporary yoga, I know that I certainly arrived at a feeling of: Let’s just give it a REST.

But as I’m wont to do, I kept on thinking about it. And today’s New York Times story about Ms. Stiles’ skyrocketing popularity has made me want to share a bit about where that’s taken me.

Because my perspective on the whole commercialization-of-yoga debate has been shifting. And since the SCS debacle was the most recent epicenter of it, it’s a good (if dicey) topic to revisit in the course of rethinking the whole thing.

So: At first, I found the and burn-bra-fat-and-become-a-size-00 marketing that I discovered in conjunction with the SCS launch horrifying. Yes, really. That’s not too strong a word. As an oldster babe in the new cultural woods that had been busily growing up around yoga while I was off practicing in my little subcultural bubble, I had really had no idea that such things were happening. So, it came as a bit of a shock.

And my gut reaction was pretty negative. This isn’t yoga! This is BAD! But then I started to realize that this is a new wave. And that maybe it’s counterproductive to fight the tide. And that maybe I should listen more closely to people who were saying that it was lifting them up and helping them. And that maybe I could learn something valuable by wading through the internal wave of discomfort and reactivity that the whole thing was generating in me.

Just to be clear, this doesn’t mean that I now buy into the view that thinking critically about what’s happening in yoga culture is “judgmental” and “un-yogic.” I still see this as a good thing, at least for those of us who are so moved.

But at some point in the midst of the whole SCS tirade, I read a blog that kinda clicked on a new light bulb for me. Someone had written about how all of this controversy about yoga being too commercial had started making her feel bad about her practice. But then finally she decided that hell, she really loved doing her vinyasa flow to blasting pop music in her Lululemon outfit – and what’s wrong with that?

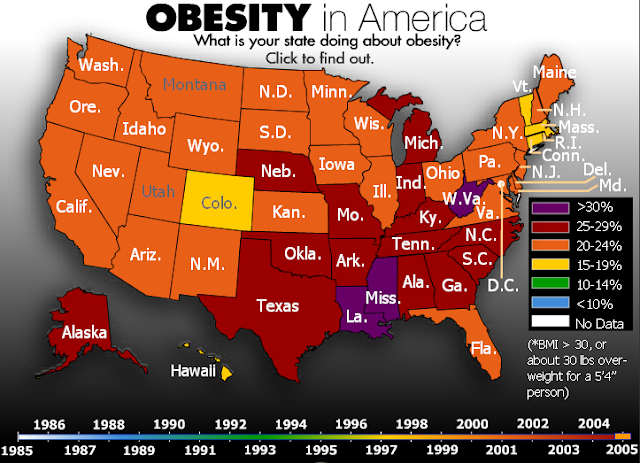

And I had to stop and ask myself, really, given all of the shit going on in the world, given how many people are overweight and not exercising at all and stressed to the max, do I really want to put my energy into taking a stand against something that’s making people feel happier and healthier? It just doesn’t seem right: kinda churlish and ungenerous, really.

But I don’t want to just “shut up and do my practice” as one friend suggested, either. Because I still think that there’s important issues at stake in this discussion. I still believe that there’s something compelling about the critiques that were made last summer (and in other iterations in the ongoing commercialization of yoga debate before then).

But I also feel that this needs to be better balanced with the equally compelling value of respecting other people’s experiences and examining the deeper nature of our own reactions.

For me, I think that a lot of my reactivity had to do with the fact that I felt like I had something personal to lose by yoga becoming a more and more shamelessly commercialized pursuit. I remember well that during the Bush II years – the politics of which I detested with heart-felt passion – I used to say that "yoga is one of the few things that I still like happening in America today.”

I felt heartsick that so much of what I loved about my country was being trashed and lost. And yoga was the one thing that I loved that was, in contrast, flourishing and growing.

So to see it seemingly swept up into the mainstream pop-cultural tide felt alarming. I wanted my subcultural refuge to remain protected, uncontaminated.

But what about all the other people out there who don’t share my alienated political-cultural views? Don’t I want yoga to be accessible to them too?

And what about the people who are just not for whatever reason ready to deal with the deeper dimensions of yoga – but who could really use some new sense of connection with their bodies, some stress relief, some physical health benefits – and maybe just some fun?

Like the lady asked, what’s so bad about that?

|

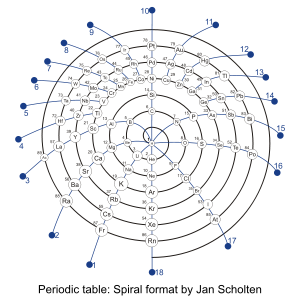

| Milky Way over Owachomo Natural Rock Bridge in Utah Wally Pacholka/Astropics.com |

Well, nothing, I think – as long as bridges to the deeper experiences of yoga continue to be strong, visible, and accessible to as many people as possible as well.

It would, I believe, be a tragic loss if “yoga lite” eclipsed the other, deeper potentialities of the practice.

And I think that we we're fooling ourselves if we believe that these bridges will appear automatically, regardless of whatever we as contemporary practitioners may do to build, destroy, or obscure them.

And I think that we we're fooling ourselves if we believe that these bridges will appear automatically, regardless of whatever we as contemporary practitioners may do to build, destroy, or obscure them.

But how to help keep them strong, visible, and accessible? It seems to me that past denunciations of “fitness yoga” have done more to build walls than bridges.

So now, I’m looking for ways to communicate about the deeper dimensions of yoga that feel more like invitations. Like opportunities. Like sightings of bridges to rich and exciting, if mysterious and often challenging places.

I know that passions run deep on questions of what yoga is, and what it could or should be. And I’m not naïve enough to think that there’s not always going to be a danger that if we discuss them, the fires they create may run out of control.

But I’m also hopeful that it’s possible to harness our passions in a way that creates a fire of collective inquiry that illuminates and maybe even warms us.

Either way though, as yoga practitioners, I don’t think that we should be afraid of playing with fire.