|

| Saluting American Yoga! with thanks to YogaDawg (July 4, 2013) |

[Note: This post was originally entitled "In Praise of American Yoga." I decided to change it in response to comments from several people who feel that the term "American yoga" is inherently offensive and objectionable. I see it as simply descriptive, and interchangeable with "yoga in America." However, titles form first impressions, which are important. So, I've changed that, but left the rest of the wording alone.]

I like to think of myself as a cultural critic. Flag-waving patriotism turns me off. Nonetheless, when it comes to the subject of American yoga, at the moment I’m feeling oddly cheerleader-prone. Why? Because while I’m all in favor of critiquing the commercialism, narcissism, and cultural shallowness that runs so rampant in American yoga culture, I’m also opposed to caricaturing the entire endeavor as the hopelessly corrupt offspring of an otherwise pristine yoga tradition.

Of course, it’s certainly true that the American yoga boom of the past 15 years has generated its own peculiar set of problems. Critical issues of commercialism, cultural appropriation, and cheapening a rich tradition absolutely need to be raised. From my perspective, the issue isn’t whether critiques of American yoga are warranted: they are. The question, rather, is how to levy those critiques constructively.

Trying to neatly separate “corrupt” American yoga from some supposedly “pure” alternative (whether Indian, Hindu, Tantric, traditional, countercultural, old school, 1990s, or whatever) is not constructive for two key reasons. First, it’s inaccurate and misleading. Real life is messy. This has always been true, both within the yoga tradition and beyond it. Second, splitting the complexities of life into all-good and all-bad categories is unnecessarily divisive, and generates unintended negativity.

Looking for Shangri-La?

Ironically, dichotomies of “pure” versus “corrupt” yoga encourage well meaning Westerners wishing to honor the yoga tradition to unwittingly reinscribe colonialist stereotypes of the “mystic East,” imagining India as a timeless, mystic land beyond the reach of modernity and even history itself. Even in the 21st century, the iconic image of Shangri-La continues to loom large in the American yoga imaginary. (A "mystical, harmonious valley, gently guided from a lamasery” featured in the 1933 novel, Lost Horizon, “Shangri-La has become synonymous with any earthly paradise, and particularly a mythical Himalayan utopia — a permanently happy land, isolated from the outside world.”)

For example, xoJane recently published an earnest article entitled "Like It Or Not, Western Yoga Is A Textbook Example Of Cultural Appropriation." The author, s.e. smith (a self-described white atheist who rejects normal gender pronouns such as “she” in favor of the gender-neutral term “ou”) shares her (or rather, ous) reservations about practicing yoga, which ou describes as “an aspect of the Hindu faith with origins that are thousands of years past.”

until very recently . . . I did asanas and pranayama myself as a way of focusing, centering, and strengthening myself. I liked how these practices made my body and mind feel, but I also felt deeply troubled by my use of some of the eight limbs of yoga in a way that didn’t feel in accordance with the practice’s roots, and by my practice of yoga as an atheist.This line of reasoning ignores the fact that the term “Hinduism” was a Western invention that lumped the disparate religious traditions of India into a single category modeled after our own monotheistic faiths. True, Indians quickly appropriated the term and used it means of building a unified national identity and fighting British colonialism. That shift, however, soon birthed a new, deliberately modernized variant of Hinduism – which, in turn, provided the cultural context for the development of modern yoga.

If I wouldn’t dream of taking Communion at a Catholic Church if I was attending as a guest, why would I practice yoga? Aren’t there lots of explicitly fitness-oriented options for me to choose from that don’t require me to appropriate religious practices from former colonies?

Given that modern yoga was intentionally crafted to speak to people of all faiths, nationalities, and cultures, ou’s feeling that ou should not practice it since ou is not Hindu is, in fact, a rejection of Indian tradition, not an affirmation of it! However, as long as India is implicitly assumed to be a land beyond history, it's impossible to imagine such a possibility, as it's based on a recognition that Indian spiritual practices (including yoga and Hinduism) evolve over time, just as they do in the West.

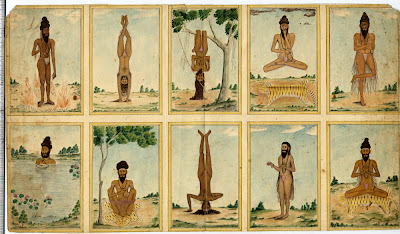

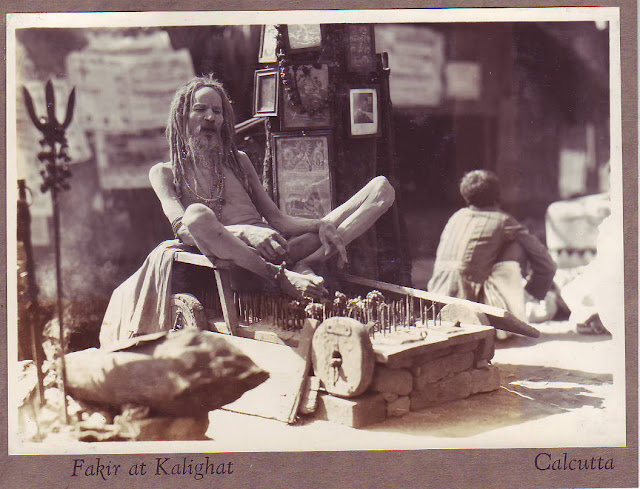

|

| Image via Decolonizing Yoga (excerpt from Yoga PhD) |

Similarly, in a recent Huff Post article, Yogi Cameron Alborzian denounces contemporary asana-based yoga on the grounds that “postures were never supposed to become the centerpiece of the entire practice, and it was only through the ego that people started to focus on them. As a result, more postures have been invented in the last few centuries.”

Again, while well intentioned, the assertion that the development of modern asana practice was solely driven by “ego” isn’t supported by historical fact. (The larger point of the article, that it’s good to move beyond a simple fixation on the body, is a good one, and particularly notable coming from an .) T.K.V. Desikachar, for example, once explained that his father, Sri T. Krishnamacharya (the most influential figure in the development of yoga as we know it today), “evolved very important principles in the practice of asana,” developing so many new postures and techniques so quickly that he was “unable to keep track of his new discoveries.”

Modern asana-based practice, in other words, was not a corruption of an otherwise pure yoga tradition produced by out-of-control modern egos. Rather, it was a deliberate reformulation of what has always been a vast and diverse tradition, re-crafting yoga in ways designed to meets the needs of the modern world.

The Pure and the Impure?

In "Stepping into the Yoga Time Machine: Before the Yogamagedon,” Chris Courtney attempts to cut the yogic wheat from the chaff in a new way. Rather than rejecting modern or even American yoga as a whole, he limits the corruption of yoga to what’s happened with it during the past 15 years in the U.S.:

Imagine a time before ex-cheerleader mean girls and lecherous douchebags had taken over yoga studios. Imagine a time when classes were harder to find, but were also less likely to suck . . . Imagine a time before yoga became an 'industry.' When there was a genuine sense of community and collaboration, rather than competition. The time you’re imagining is the late 1990s in America.While I appreciate the desire to lambaste the slavish commercialism that’s become more and more present in American yoga culture, neatly dividing recent history into the “good” yoga of the 1990s versus the “bad” yoga of today is absurd. I’ve heard enough stories about L.A. yoga culture in the 1990s to believe that this idyllic time of “community and collaboration, rather than competition” didn’t exist. My best guess would be that then, like now, the yoga world contained pockets both of cut-throat competition and inspiring cooperation. In most cases, however, I suspect that people found themselves spending a lot of time in that big, grey area in between.

. . . When I think of what we’ve allowed yoga in America to become, it seems that instead of holding steady in our practice to consciously navigate our way through the Kali Yuga, we’ve doubled down on its worst aspects. With every new yoga fad, gimmick, or distraction from the practice, we’re moving farther from the divine and speeding our own degeneration.

Similarly, the idea that we’re speeding away from “the divine” and toward “our own degeneration” is a bit much. It's worth noting that there have been some positive developments that didn’t exist in the 1990s: the yoga service movement, the expansion of yoga into prisons and other major social institutions, the explosion of the yoga blogosphere, the development modern yoga studies, the integration of yoga with somatic psychology, the development of trauma-sensitive yoga, and the expansion of female leadership, to name a few.

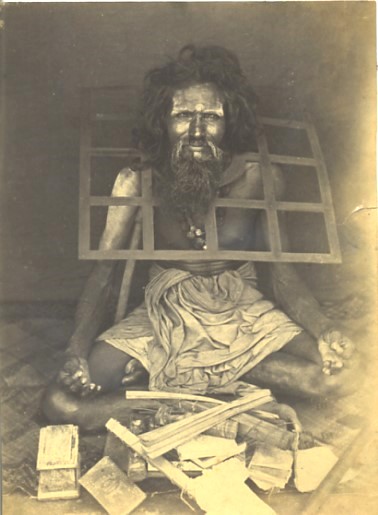

|

| Back cover image: 21st Century Yoga c. Sarit Z. Rogers / Sarit Photography |

Problems of Polarization

Since I'm sympathetic to the critical project, I wouldn’t be harping on the need to be more balanced if I wasn’t concerned that the public conversation about yoga has started to become overly polarized. Not long ago, we had the opposite problem: except for a few lone bloggers, yoga discourse seemed firmly sealed in a big, pastel-colored bubble, in which no negative observations were allowed. Now, the bubble has clearly burst – and that’s a good thing. The question, however, is how to build an inclusive conversation that balances honesty and critique with respect for diverse experiences, commitments, and points of view.

While it takes a variety of forms, there’s a recurring tendency to try and divide the sprawling, vast, diverse world of yoga into fixed camps with clear boundaries separating the good from the bad, the commercial from the authentic, and the pure from the corrupt. I believe that it’s important to resist these tendencies toward neat categorization, which present an inaccurately simplified view of reality, and promote interpersonal division.

Of course, it’s tempting to pit “commercial yoga” against “authentic yoga" (or whatever) to dramatize a valid critique. Yet setting up such hard-and-fast categories carries a cost. Dividing the yoga community into a good “us” versus a bad “them” encourages self-righteousness on the “us” side by creating a stereotyped “Other” to measure one’s superiority against. At the same time, it tends to generate hurt, anger, resentment, and/or alienation among “them.” Once such dynamics are in play, the negative blowback overshadows whatever good may have been intended by the critique.

For Americans in particular, there are also big problems with the social ethics of such “corrupt vs. pure” paradigms. Writing off contemporary American yoga as hopelessly tainted provides an excellent rationale for immersing oneself in a yoga subculture that’s uninterested, if not actively resistant to connecting with others in our society. At the same time, it undermines faith in our ability to confront with the enormous challenges of our particular time and place.

Given the sorry state of our country at this time, I personally feel that those of us lucky enough to have received the gifts of an effective yoga practice would be better off seeking ways to share this knowledge with others. Doing this, however, requires accepting the realities of American yoga and the society it’s part of in all of its maddening messiness and contradictory complexity. This doesn’t mean dropping critique or embracing the lazy apathy of “it’s all good." It does, however, require tempering criticism with concern for others who may not share our perspectives or commitments, yet still in their own way love yoga as much as we do.